Cowã¢ââ¢s Skull Red White and Blue the Metropolitan Museum of Art the Met

Teach close reading skills, the ability of particulars, and America'due south enduring spirit with Georgia O'Keeffe's Moo-cow's Skull: Red, White, and Blue

Moo-cow Skull: Scarlet, White, and Blueish is part of The Met'south drove. Encounter their website for detailed information. Click on the painting for a high quality prototype.

Moo-cow Skull: Scarlet, White, and Blueish is part of The Met'south drove. Encounter their website for detailed information. Click on the painting for a high quality prototype.

As I was working I thought of the city men I had been seeing in the Eastward. They talked so frequently of writing the Great American Novel — the Dandy American Play — the Bang-up American Poesy. People wanted to "do" the American scene. I had gone back and along across the state several times past then, and some of the electric current ideas well-nigh the American scene struck me as pretty ridiculous. To them, the American scene was a dilapidated house with a broken down buckboard out front end and a equus caballus that looked like a skeleton. I knew America was very rich, very lush…Well, I started painting my skulls around this time.…I had lived in the cattle country—Amarillo was the crossroads of cattle shipping, and you could see the cattle coming in across the range for days at a time. For goodness' sake, I thought, the people who talk about the American scene don't know annihilation nigh information technology. So, in a fashion, that cow'south skull was my joke on the American scene, and it gave me pleasure to make information technology in red, white, and blue.

— Georgia O'Keeffe, describing the genesis of her painting in an exhibition catalogue

I painted my cow's head because I liked it and in its style it was a symbol of the best part of America I had found. Cattle were important to America, as I knew from my days in Amarillo when they were only beginning to call back about oil. I thought to myself 'Simply for fun I will make it cherry, white, and blue–a new kind of flag almost.' It always amused me as my idea of something American.

— Georgia O'Keeffe, in a letter of the alphabet to Anita Pollitzer, 1931

I have wanted to paint the desert and I oasis't known how. I ever think that I cannot stay with it long enough. And so I brought home the bleached bones as my symbols of the desert. To me they are as beautiful as anything I know. To me they are strangely more living than the animals walking around—hair, eyes and all with their tails switching. The bones seem to cut sharply to the eye of something that is keenly alive on the desert even tho' information technology is vast and empty and untouchable—and knows no kindness with all its beauty.

— Georgia O'Keeffe, "About Myself" in Georgia O'Keeffe: Exhibition of oils and pastels.

New York: An American Identify; 1939

Expect at Moo-cow's Skull: Red, White and Bluish. Before reading the excerpt above, tell students the title of the piece and enquire what is going on in this picture? This regional portrait has familiar imagery that is open up to nuanced interpretations. Come across how much students can decipher through a grouping discussion. Encourage students to place the evidence that supports their reasoning. Students should likewise be encouraged to share wonderings and vocalism confusions. As the chat slows, explicate you are going to read how the artists described the motivations and intentions that guided this painting. Later on reading the excerpts inquire how does this new insight change your understanding of the painting?

Annotation: To facilitate give-and-take, you may want to innovate students to the term supraorbital foramen. Those are the ii prominent holes above the cow's center sockets (human's as well) that aqueduct the claret vessels and fretfulness to the forehead. Supra is from the Latin meaning "to a higher place or over." Orbit is a medical term for the "bony socket of the middle." Foramen is a medical term for a natural opening or passage, especially one into or through a bone.

Begin with art history

Georgia O'Keeffe was built-in in Sun Prairie, Wisconsin in 1887. The O'Keeffes impressed upon their vii children the demand to be well educated. So, when Georgia expressed an interest in the arts her mother bundled art lessons with a local artist. Georgia continued to study art throughout her early on schooling. To support her academy studies and art making, O'Keeffe traveled effectually the United States working as a commercial creative person and an art teacher. O'Keeffe was initially recognized for her nature studies and realistic painting techniques. In time she experimented with her own unique brand of abstract compositions.

In 1916 a friend of O'Keeffe shared a serial of her abstruse drawings with Alfred Stieglitz, an influential art dealer and photographer. Captivated by these drawings, Stieglitz immediately exhibited her work. Their shared involvement in art grew into a deep personal relationship and, even though he was 23 years her senior, they married in 1924. Annual exhibits at Stieglitz's galleries helped cement O'Keeffe's reputation in the established art world. During this time period Georgia was all-time known for her large dramatically colored paintings of flowers. While her piece of work and popularity flourished, Georgia resented the gender stereotypes and Freudian interpretations imposed on her work by patronizing art critics. Georgia expresses these frustrations in an exhibition itemize,

A flower is relatively small-scale. Anybody has many associations with a flower — the thought of flowers. You put out your hand to touch on the blossom — lean forward to odour it — maybe impact it with your lips about without thinking — or give it to someone to please them. Still — in a way — nobody sees a flower — actually — information technology is so small — nosotros haven't time — and to see takes time, like to have a friend takes time. And so I said to myself — I'll paint what I run across — what the flower is to me only I'll paint it big and they will be surprised into taking fourth dimension to look at it — I will brand even decorated New-Yorkers take fourth dimension to see what I meet of flowers. Well — I made you take time to await at what I saw and when you took time to actually notice my flower, you hung all your ain associations with flowers on my flower and you write about my flower as if I think and run into what you think and meet of the flower — and I don't.

In 1929, feeling hemmed in by Stieglitz'south social circumvolve and looking for a new source of inspiration for her work, O'Keeffe travelled with a friend to New United mexican states. The landscape, architecture, and indigenous cultures refreshed her and refined her visual vocabulary. She witnessed Navajo rituals and traditions. She was immersed in the Catholic symbols and structures prevalent in the Hispanic communities. And, she experienced the Southwestern cowboy culture. Cow Skull: Red, White, and Bluish grew out of these influences and evoked the contradictions inherent in American society as the abundance of the Roaring Twenties gave way to the Nifty Depression and an unforgiving Grit Bowl that ravaged the farms and ranches of the American Southwest. By integrating these cultural references into a expressive nature study, O'Keeffe melded naturalism and nationalism, creating an iconic portrait of America'southward enduring spirit.

In blending realism and abstraction, O'Keeffe'due south paintings brought majesty and spirituality to common natural objects—flowers, leaves, shells, stones, and bones. And while her simplified representations of New Mexico's landscape and architecture aligned O'Keeffe with the regional art movement, her innovative style spoke to more than universal modern art concerns and earned her the moniker the "Mother of American modernism."

Wait like an art critic

Moo-cow Skull: Red, White, and Blue is role of The Met's collection. Run across the Metropolitan Museum of Art'southward website to learn more. For additional insight visit the Georgia O'Keefe Museum.

Comparing Realism and Abstraction

Nothing is less real than realism. Details are confusing. Information technology is only by selection, by emptying, past emphasis, that we get at the real meaning of things.

— Georgia O'Keeffe

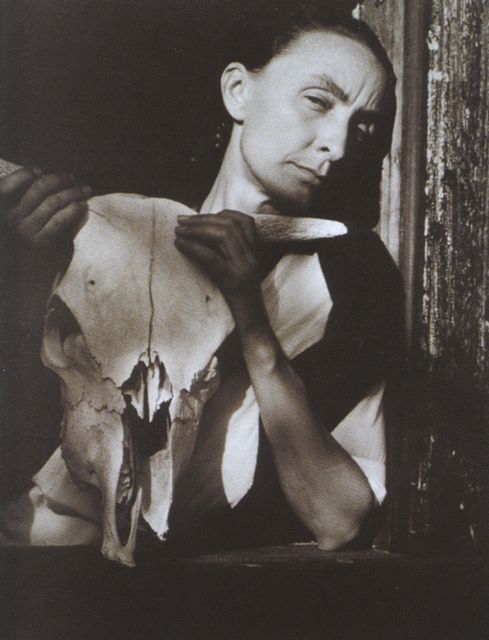

Indicate out and discuss: When O'Keeffe returned to New York with a barrel total of bones, her husband, Alfred Stieglitz, was as captivated by the skulls as O'Keeffe was and photographed Georgia with them. Compare O'Keeffe's cow skull painting with the photograph of O'Keeffe belongings the same cow skull. How is the rendering of the cow skull in the painting unlike than the cow skull shown in the photo? How does O'Keeffe's transformation of the cow skull provide added meaning?

Turn, Talk, and Study Back (Possible answers: The painted skull is prominent and celebrated. Information technology commands the limerick looking directly at the viewer. The photographed skull is more of a prop, juxtaposed with Georgia. The painted skull appears more bleached and pristine, while the photographed skull has more than shadows and seems gritty, like an celebrated relic. The painted skulls even, radiant lighting seems supernatural. The painted skull is elevated in the limerick. Centered horizontally the skull'south horns reach out to the edges of the painting. The photographed skull rests heavy and low on the windowsill, off middle, sharing space with Georgia. The elevated skull is more than crucifix-like, sitting high on a cross with the horns extended like arms. This lighting and bearing makes the painted skull seem sacred. The painted skull is a sacred icon, while the photographed skull is a quaint antiquity.)

Regional Imagery

Bespeak out and discuss: Moo-cow Skull: Cerise, White and Blue is layered with cultural associations—Native Americans, Hispanics, and cowboys. Have students review the historic and gimmicky images in the gallery above and links below, and identify elements and references the painting may draw on.

- Images 1: Julian Martinez' hide painting Buffalo Dancers (@1930s) shows how native cultures have traditionally used ceremonial animal masks. Click on this link to come across videos of gimmicky Cherokee Eagle Dancers.

- Images two: Navajo chief'southward wearing blankets are the most recognizable and prized of all Navajo weavings. They come in four phases. The Offset Phase blueprint is composed of horizontal bands of alternating colour at top, eye, and lesser. Jalucie Marianito shows her contemporary kickoff phase weaving. Here is a concise video tutorial on Navajo primary's wearing blankets.

- Images 3 and 4: Early Spanish colonization introduced Catholicism to New United mexican states. Religious symbols such every bit the crucifix and the cantankerous are mutual in Hispanic communities.

- Images 5: Romantic visions of cowboy life inspired dude ranches throughout the due west, including New Mexico. Symbols of the rugged "wild west," including animal skulls, are common decorations from the earliest times to the present day. The early flick is of the Eaton brother'due south and their families at Custer Trail Ranch in the Dakota Territory, 1 of the earliest dude ranches (1890). For a contemporary employ of skulls see a cabin at the Granite Creek Ranch, a 6th generation working cattle ranch in the mountains of Eastern Idaho.

What southwestern cultural associations tin can you run across in Cow Skull: Red, White, and Blue? How practice these visual references add together significance and pregnant to the painting and how do they support O'Keeffe's intentions?

Turn, Talk, and Study Dorsum (Possible answers: Like the ceremonial dancers who prefer an creature's prominent features to create a spiritual connection, the painting makes the moo-cow's skull a sacred icon. The supraorbital foramen are depicted with dramatic shadows making them look similar a second ready of optics. This double-center consequence is compounded past the red china white forehead that sits on top of the darker fractured face. This evokes the mask the eagle dancer peers out from nether. While the red, white, and blueish coloring evoke the American flag, the stripes on the painting as well call to listen the alternating bands on the Navajo Chiefs Coating. The bluish-white field with the diagonal lines look like the shadows on the blanket held out in the brilliant dominicus. The skull with the extended horns hovering on superlative of a black vertical band could be seen like a crucifix. In this light the brow could be read as a torso and the supraorbital foramen as nipples. The dark vertical band with the prominent scissure that splits the skull and the perpendicular lines created past the horns create a cantankerous-like composition. The cow skull in the painting and the skulls on the dude ranches evoke romantic images of the Wild West, nostalgia for cowboy life, and the bountiful only unforgiving environment. On a dude ranch wall animal skulls hang as trophies, symbols of man'south conquest over nature. Together these shifting cultural elements evoke the complex societies of the southwest. They intertwine, creating a cohesive compelling image with a magical spiritual aureola, much like the way Georgia saw the indelible American spirit.)

Expressive Oppositions

Point out and discuss: In creating her "Slap-up American Painting," O'Keeffe didn't desire to create a simplistic image of "a dilapidated firm with a broken down buckboard out front end and a horse that looked similar a skeleton." Rather, O'Keeffe recognized that a deep understanding of America meant you appreciated its layers and paradoxes, such as, a country of immigrants that loathed foreigners; a proudly democratic nation that actively restricted the voting rights of big sections of its denizens; and an affluent gild and a world superpower caught in the grips of a Great Depression. As a subject, the moo-cow skull was open to varied, and fifty-fifty opposing interpretations. Have modest groups of students select a pair of opposing terms from the listing below and explicate how they could both use to Moo-cow Skull: Crimson, White, and Blueish—death/eternal; common/sacred; fragile/durable; specific/universal; minor/monumental; and ugly/beautiful. How practise these visual contradictions add significance and meaning to the painting and how exercise they back up O'Keeffe's intentions?

Turn, Talk, and Report Dorsum (Possible answers: Death/Eternal: The skull is a symbol of death, like a pirate's flag or toxicant. The skull in the desert comes from a cow that died and then decomposed. The decomposition of the cow also touches on the eternal as it fits inside the ongoing bicycle of life as the cow is consumed past the state on which it fed. While the cow has died, its skull lives on as an artifact of the landscape and now equally a work of fine art. Common/Sacred: The skull is mutual, evoking a typical domesticated animal. Cattle are grown like any other mass-produced food item. Skulls are a standard decoration in some cultural settings. Information technology's a natural occurring detail almost akin to sticks and stones. The manner O'Keeffe treats the skull makes it sacred. She makes the viewer reflect on it, imbuing it with added significance. Information technology is elevated in a cross-similar way. The pristine white of the skull is accentuated making it like a religious icon. These visual contradictions add complexity to the painting encouraging multiple levels of interpretation. Equally a portrait of America's enduring spirit, the multiple interpretations evoke America'southward own complexity and inherent contradictions.)

Think Like an Artist

My 2d year of loftier schoolhouse, my brother and I lived with our mother's younger sister in Madison. The art teacher was i of those sparse bright-eyed women that I take always since associated with the thought of an Art Instructor. She wore her lid in schoolhouse—a chapeau made all of artificial violets.…She is very vivid to me continuing in front of the class—her hat of violets and a fresh spring feeling virtually her costume. Belongings a Jack-in-the-pulpit loftier, she pointed out the strange shapes and variations in color—from the deep, about black earthy violet through all the greens, from the stake whitish green in the blossom through the heavy light-green of the leaves. She held up the purplish hood and showed us the Jack inside. I had seen many Jacks earlier, but this was the first time I remember examining a bloom. I was a piffling annoyed at being interested because I didn't like the teacher.…But maybe she started me looking at things—looking very advisedly at details. Information technology was certainly the beginning time my attention was called to the outline and color of any growing thing with the thought of drawing or painting it.

— Georgia O'Keeffe, in her autobiography

This lesson in magnifying and analyzing natural objects initiated an art practice that O'Keeffe employed throughout her career as she rendered flowers, shells, and bones. If it's good enough for Georgia O'Keeffe why not give it a try. Encourage students to collect a small natural object of personal significance and then render it fully on a large surface noting and amplifying subtle shifts and details. Rolls of butcher paper with charcoal sticks or magic markers on a whiteboard will practice—just work large. Challenge students to work like O'Keeffe and consider the abstract limerick of the overall nature portrait, as well as its characteristic features.

Life Lesson

You paint from your subject, not what yous encounter…I rarely paint annihilation I don't know very well.

—Georgia O'Keeffe

Recognize the universal in the specific. Georgia O'Keeffe created universally appealing art from her deep personal experience with a specific locale. James Joyce expressed a similar desire to create from an intimate sense of identify. "For myself, I ever write about Dublin, because if I can become to the centre of Dublin I can get to the heart of all the cities of the world. In the particular is independent the universal." Rosanne Cash echoed this sentiment in describing her album inspired past her travels in America's Deep South, "The more specific you are near places and characters, the more than universal the song becomes." The poet Robert Pinsky takes an even more expansive view and contends that if you could empathise an artifact or an idea well plenty information technology would be a portal into the whole residue of the universe. These writers share the understanding that the more specific and physical you are with your words and examples, the more than relatable and far reaching your message can be. Then whether you are in the expressive arts, building a brand, or promoting a cause, tell a memorable story with such personal conviction and detail that it taps into the universal.

Related Video

- Georgia O'Keeffe Talking about Her Life and Work (Part ane) (4:24) describes the motivations and influences that shaped her earliest bone paintings including Cow Skull: Red, White, and Blue.

- Georgia O'Keeffe: By Myself BBC Documentary 2016 (1:04:32) offers a comprehensive overview of O'Keeffe's life and work with many celebrated images and immediate accounts by Georgia, her family unit, and friends.

- Georgia O'Keeffe a Life in Fine art (13:39) is a documentary by the Georgia O'Keeffe Museum and offers a concise overview of O'Keeffe's art and relationships.

Integrating into Your Curriculum

Artists often apply common visual strategies or signposts to alert viewers to meaning details in their fine art. Here are some ideas for using these visual signposts to unpack a work of fine art. Remember, the close reading skills in art appreciation are similar to the close reading practices taught in reading.

Literature Links: What piece of literature would you partner with Georgia O'Keeffe'south Cow Skull: Crimson, White, and Bluish? Cow Skull: Red, White, and Blue could inform other regional literature from the time period.

- Willa Cather's Death Comes for the Archbishop (1927) recounts the efforts of two rogue priests who abuse church tenets and the natives every bit they establish a diocese in New Mexico Territory. There are rich parallels in the way Cather marries journalistic objectivity with a subjective indicate of view and the way O'Keeffe marries realism and brainchild.

- Sanora Babb's Whose Names are Unknown chronicles the struggles of the Dunne and Starwood families, High Plains farmers who fled drought dust storms during the Slap-up Depression.

- N. Scott Momaday's Business firm Made of Dawn (1968) is a redemption story of a Pueblo Indian who loses his way after the traumas of World War Ii and uses traditional rituals to observe his way back to the land and his civilization.

- Frank Waters' The Man Who Killed the Deer: A Novel of Pueblo Indian Life (1942) is the story of a rebellious Pueblo Indian haunted by the spirit of a deer he killed out of season (white law) and without ritual respect (native constabulary). This story virtually sin and redemption explores Pueblo Indian values and their connexion to the land.

Writing Opportunity: The Rule of Write About a Pebble. In his poem Paterson, William Carlos Williams wrote the now famous rallying cry of poets and artists alike, "Say it, no thought but in things." In the manner they both pursue this idea, master writing teacher Nancie Atwell and Georgia O'Keeffe prove to be kindred spirits. They both recognize the demand to get beyond the full general, and focus instead on specific observations and experiences. This lesson is based on Nancie Atwell's lesson "The Rule of Write Near a Pebble."

Don't write about a general idea or topic; write about a specific, observable person, place, occasion, time, object, brute, or experience. Its essence will lie in the sensory images the writer evokes: observed details of sight, sound, smell, touch, taste; and stiff verbs that bring the details to life.

- Don't write well-nigh ________(pebbles). Write about a ________ (pebble).

- Don't write about fall. Write about this autumn day. Go to the window; go outside.

- Don't write nearly sunsets. Write about the amazing sunset you saw last night.

- Don't write about dogs or kittens. Observe and write about your dog, your kitten.…

— Nancie Atwell, from her teaching resource Lessons That Change Writers.

Click this link to see how Georgia O'Keeffe's Cow Skull: Scarlet, White, and Bluish can be used to teach elaboration and how to make the almost of meaningful details.

How would you use this painting to build on one of your units of study? Please share if you lot have other ideas on how to teach Cows Skull: Cherry-red, White, and Bluish by Georgia O'Keeffe equally an English/language arts lesson plan.

Source: https://charlesmcquillen.com/georgia-okeeffe-cows-skull-red-white-and-blue-english-language-arts-lesson-plan/

0 Response to "Cowã¢ââ¢s Skull Red White and Blue the Metropolitan Museum of Art the Met"

Enregistrer un commentaire